Understanding Animal Research (“UAR”) has re-highlighted one of its propaganda pieces from 2017, entitled “Why the anti-vivisection movement took an absolutist view”. Just like the other publications pushed out by this leading lobbyist and trade association for the animal research industry, this post misleads, misdirects, and misinforms.

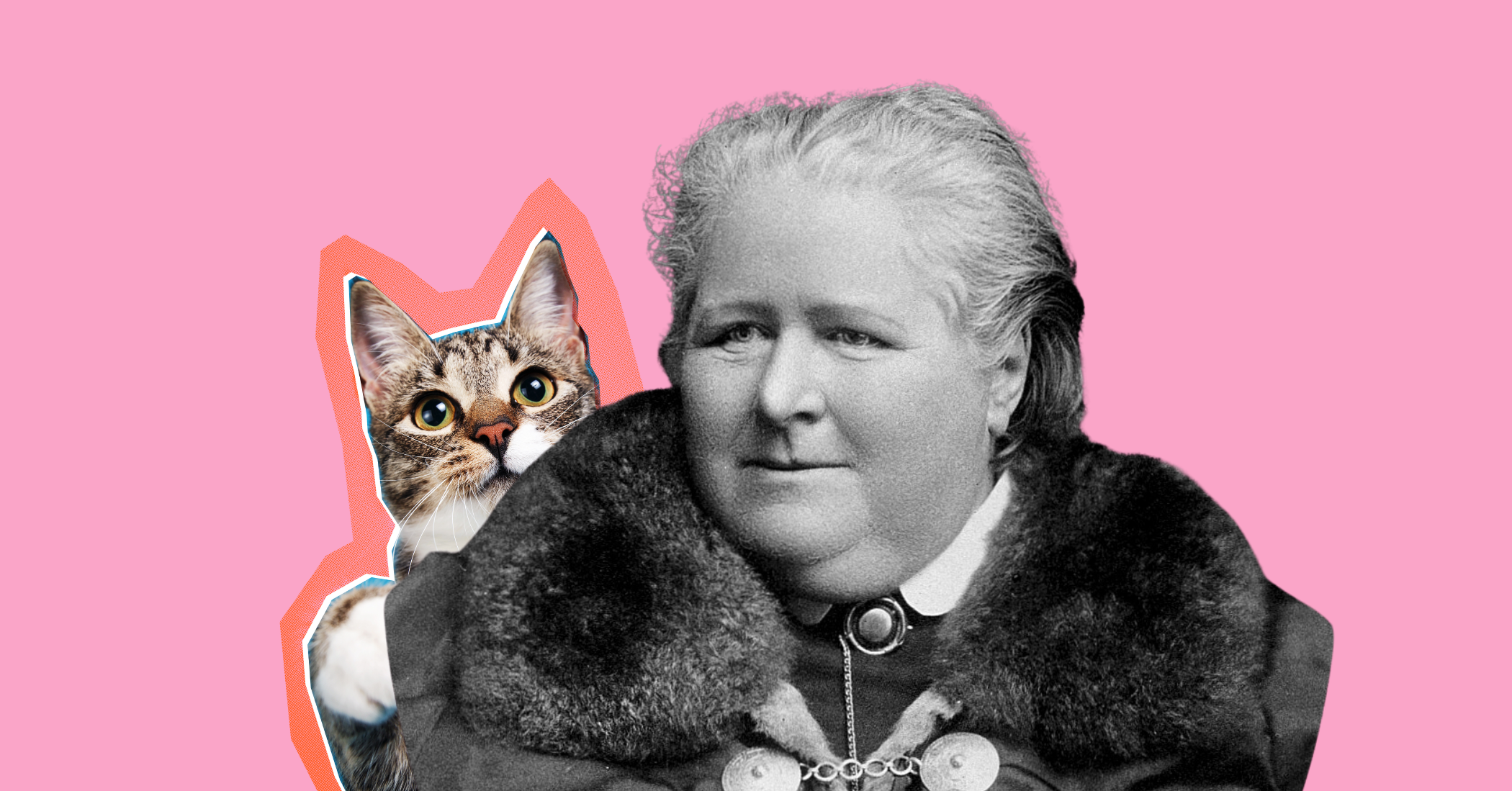

UAR tries to impugn the reputation and sensibilities of Frances Power Cobbe, a British activist and philanthropist often credited with initiating the anti-vivisection movement.

Cobbe is a major historical figure in the animal protection movement, and UAR may well be particularly bent on discrediting her because she is considered by many to be the mother of the modern anti-vivisection movement.

Cobbe was a “moral reformer”, an intersectionalist (emerging from the feminist movement to spend the second half of her life championing the interests of other-than-human animals), and a tenacious, savvy advocate, who successfully motivated concern for animal experimentation among both the aristocracy and the public “all over the Western world”. Indeed, Cobbe proved to be such a force that animal researchers had no choice but to reckon with her themselves, forming groups to “counter” her “growing influence” and “promote the interests of animal researchers”. Unfortunately, as we who stand in the fight today know, the animal researchers prevailed, having pooled their vast resources and political connections to convince much of the public that Anti-vivisection was a community conspiracy.”

Yet, over a century later, the animal research industry – as represented by UAR – still hasn’t forgotten about Cobbe or given up on trying to discredit her.

UAR accuses Cobbe of pursuing an end to animal research out of selfishness.

That’s right, UAR argues that Cobbe’s advocacy caused “more animals to suffer” and represented her choosing “her soul over [the animals’] wellbeing”. As thin as it is preposterous, this argument is nothing more than a version of “I know you are, but what I am?” – indeed, Cobbe did not shy away from writing about the selfishness of humans who supported vivisection; said she: “The bribe here offered to human selfishness is an ingenious one. ‘Let us,’ the physiologists say, ‘retain the right to put animals to torture, for it is very “remarkable” that when we do so it is always in your interest!’”

Moreover, UAR’s argument is, in many ways, the same argument made against animal rights advocates today – that we should concern ourselves with how animals are used, commodified, exploited, harmed, and killed, rather than that they are used, commodified, exploited, harmed, and killed in the first place. Such a focus is of huge attraction to the animal research industry because, of course, it dispenses with the most fundamental question – effectively conceding that the use of other-than-human animals as means to human ends is ethical. Only it’s not.

The true animal rights movement (including Rise!) knows that Cobbe was right to pursue abolition and does the same.

Interestingly, Cobbe began as a welfarist, an advocate for reforming and restricting the practice of vivisection (not outright prohibiting it). But, her varied and prolonged experiences at the forefront of the reform movement – including repeated, failed attempts at securing the passage of legislation to meaningfully regulate the use of animals by labs – spurred her to reject reform (or welfarism) in favor of abolition (or animal rights).

She came to believe that anti-vivisection advocates would never succeed in freeing animals from labs if they did not fully oppose the practice. And, in doing so, it can be argued that Cobbe returned to her roots – indeed, her middle name, Power, was “her inheritance from her family, carved in wood above her great grandfather’s chair”, which read: “‘Deliver him that is oppressed from the hand of the adversary.’”

And, the animal research industry knows Cobbe was right, too – for it fights only that which poses a threat.

No history of the anti-vivisection – and, by many accounts, the animal rights – movement is complete without Frances Power Cobbe, and UAR’s continued preoccupation with her only proves this point. Far from a mere “140 year hissy fit”, as UAR dismissively (and disingenuously) terms it, Cobbe launched a social movement that remains as necessary, relevant, and worthy today as it was at inception.

Moreover, if anyone is having a hissy fit, it’s the animal research industry . . . perhaps finally recognizing that one person can make a transcendent, enduring difference, and that we who follow won’t stop until every lab cage is empty.