In celebrating moms on Mother’s Day, we are reflecting on the sacred and incomparable bonds that exist between all species of mothers and their children.

We are also dreaming of a world in which maternal bonds are honored and protected, not — as is done every single day in our world’s animal laboratories — unjustifiably severed.

For at least the last 100 years, animal researchers have “routinely separate[d]” newborns from their mothers to, they say, “study[] . . . the reactions (and consequences) for the newborns and their mothers”.

The most famous examples of such emotional and psychological horror were conceived of and directed by Harry Harlow, a University of Wisconsin animal researcher and National Medal of Science recipient whose “[s]tudies of the mother-infant bond made him one of the most influential, and most controversial, figures in modern science.”

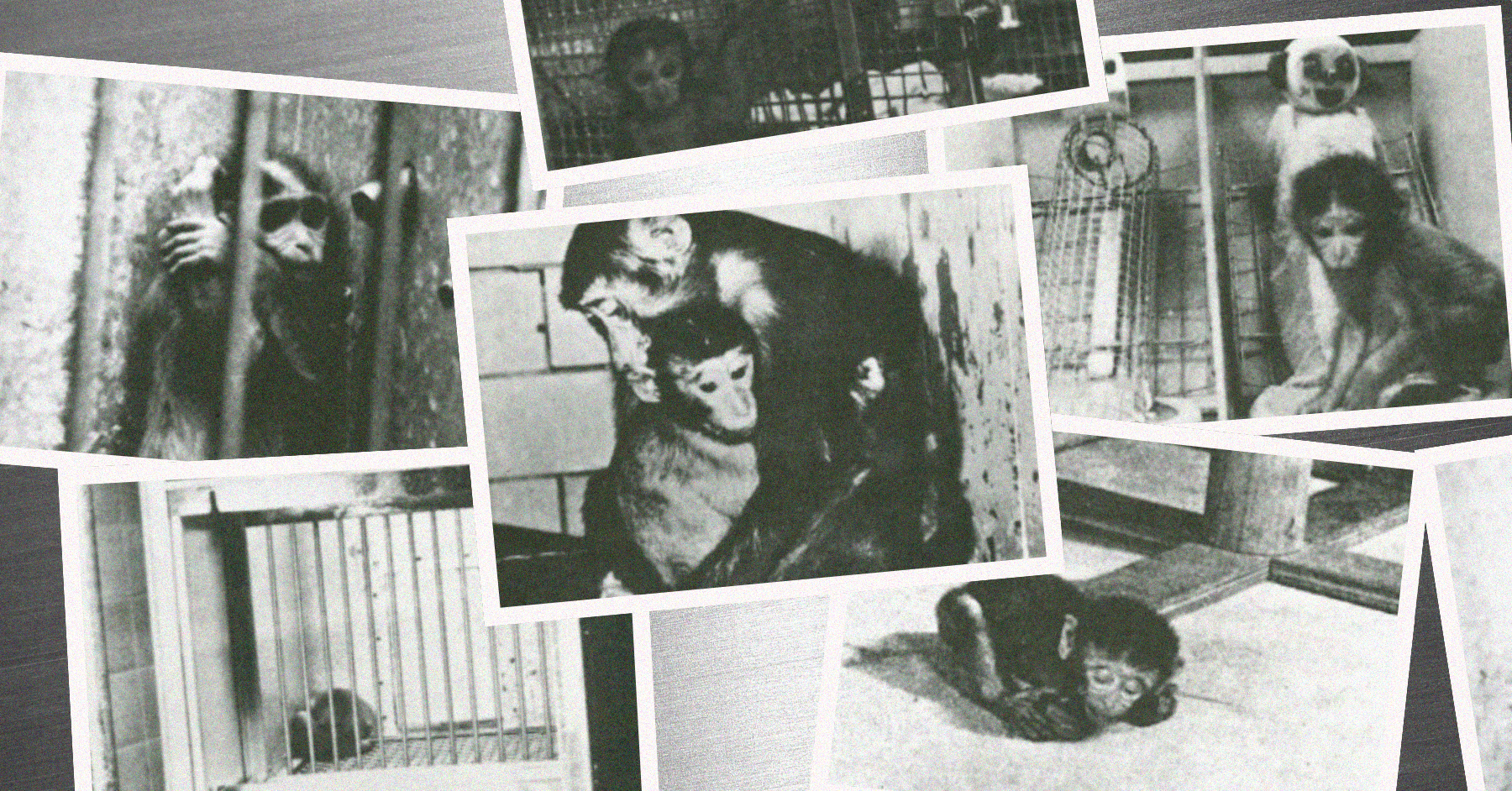

Harlow’s experiments victimized rhesus macaques, and, though he regarded them as nothing but “tools” who were “easy to use”, he also “reported that —in the days before wide use of anesthesia — it sometimes took two lab workers to hold the struggling mother down while a third pulled the baby away.”

This means that it took three, adult humans to remove a tiny baby from an approximately 12-pound monkey.

Just like human mothers, macaque mothers fight with all their might to protect their children; and just like human children, macaques desperately need to be with their moms.

In an early experiment, students slipped a clear plastic shield between mother and baby monkey. The mothers raged, screaming at the researchers, pacing an angry path. The babies tried – as confused birds will smash into glass windows – to go right through the barrier. When it failed to give, the infants huddled against the plastic, as close to their mothers as they could get, and cooed to them – calling and calling – until the divider was removed.

Later experiments saw the babies permanently separated from their mothers. The mothers grieved, and, as Harlow found, the babies suffered “emotional” and “mental” destruction. “Even when placed later with other animals, they sat staring blindly through the bars as if alone”, and Harlow “complained that they might as well be stone sphinxes”. Of course, this information did nothing to prompt Harlow to question the ethics of what he was doing – instead, his team continued with these experiments, (callously and deplorably) incorporating this early knowledge by naming orphaned and isolated baby monkeys after stones (e.g., Millstone, Grindstone).

Harlow next created cruel “surrogate” mothers and “perfectly vicious mother[s]”, reporting that, no matter what he did, he could still not “drive the infant away, short of killing it”.

Harlow “built a surrogate that blew blasts of pressurized air onto the clinging infant, whipping against the little animal so hard that the hair would be flattened to its body.”

He “created a [surrogate] mother who shook, rattling the baby back and forth until its teeth would literally chatter in its mouth”.

He developed a “surrogate mother” that “contained a catapult that would send a small monkey flying across the cage”.

He generated a “series of mothers whose blood ran truly cold; it was almost ice water. The infants’ responses were so severe that one died almost immediately; others curled themselves up in corners, refused to eat, becoming severely dehydrated.”

He constructed a “surrogate” he “nicknamed ‘the iron maiden”, which featured “retractable brass spikes that could be stabbed into the infant as it clung”:

Harlow called these the evil mothers. He discovered that the [babies] had an unwavering loyalty to them. Even with the iron maiden, even when the infants would skitter away, screaming with shock, they would stop, hesitate, watch until the spikes retracted, return to cling again . . . This was its mother after all, and she–be she flesh and blood or wire and spikes–was all that baby had.

“Virtually all of the infant monkeys were, in Harlow’s own words, ‘terrorized’….”

Harlow’s “surrogate mothers” did not prove to be, as he had boasted, ‘mother machines’ that were superior to real mothers”.

And, the infants “reared with inanimate surrogate mothers” – even those that did not cause them direct physical harm – “became as psychologically disturbed as infants reared alone”. They would, among other abnormal and devastating behaviors, “‘chew[] or tear[] at [their own limbs] with their teeth to the point of injury’….”

Animal researchers continue Harlow’s and his disciples’ barbarous “work” (in addition to revering Harlow’s legacy), despite admissions that “‘infant primates and their mothers suffer greatly when separated’”.

To make matters worse (if that’s even possible), the justification for Harlow’s experiments (i.e., that were relevant to human mental disorders) proved entirely invalid, as the experiments failed to benefit humans in any meaningful way:

The results of this research have had little impact on clinical practice, and the potential for future advances seems limited. Many experiments were trivial extensions of past research, or simply were attempts to reproduce in animals what was already known about humans.

This has led some experts to suggest that “the greatest Harlow legacy to science is a generation of researchers who don’t know how to do anything but redo aging experiments”, who “‘make a career out of endless variations on a theme,’….”; and that this “endurance of the primate separation experiments should serve as a clear illustration that science is a business, like any other endeavor. That scientists are in the business of raising money for their work. And if they find a profitable line of experiments, they will stick with it….”

. . . it’s like a joke with a bad punch line: ‘Q: How many monkeys does it take to convince scientists that baby animals are stressed by being taken away from their mothers? A: As many monkeys as the government will buy for them.’

There is a very real risk (if not a likelihood) that Harlow-inspired studies will “drag on indefinitely, with yet more species, more diverse situations, and more procedures being tested. Indeed, recent reviews of separation experiments state that many more experiments need to be conducted.”

Salaries are getting paid, after all. Consider just one, modern-day example: Harvard University vivisector Margaret Livingston, who has received over $32 million from the NIH since the 1980s and continues to make a living “taking infant macaques from their mothers shortly after birth and attempting to appease the mothers’ distress by giving them plush toys as ‘surrogate infants.’” She, then, uses the infants for various experiments, including “to study recognition by depriving them of the ability to see faces, either by sewing their eyes shut or by requiring staff to wear welders’ masks around them”, or by “implant[ing] electrode arrays into the monkeys’ brains”.

Similar research is simultaneously being undertaken by countless other animal researchers, who are victimizing countless other species.

So, even though Harlow has “become known as a prime example of the cruel and thoughtless animal researcher”, he *just* displayed the very same self-interest that today’s animal researchers display. Said Harlow, “‘[t]he only thing I care about is whether the monkey will turn out a property I can publish.’”

And that’s where we — humans who care about monkeys (and all other-than-human animals) themselves — come in.

We must reframe Harlow’s legacy — aptly described as “unthoughtful sledgehammer attempts to solve complex human problems” — around the very ethics his work violated.

We must bring to life the assertion that the “chief contribution” of Harlow’s and his disciples’ pseudo-science is to be found in “ethics” itself — that is, in recognition and rejection of humans’ cruel “use of and disrespect for other sentient and intelligent beings”.

And, we must stop the self-perpetuating, unscrupulous animal research industry from breaking any more maternal bonds. We hope you will join us in protecting the bond between all mothers and their children.

Feeling inspired to help end animal experimentation? Take one minute to help deter $10 million taxpayer dollars planned to be spent on nonhuman primate breeding and experimentation.

Please help to spread the word. Share this important blog with your friends on Facebook and X (Twitter) now. Thank you.